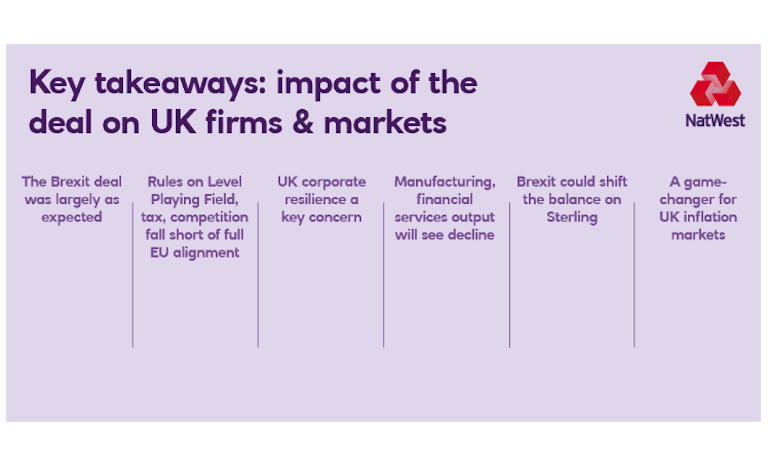

Trade in goods

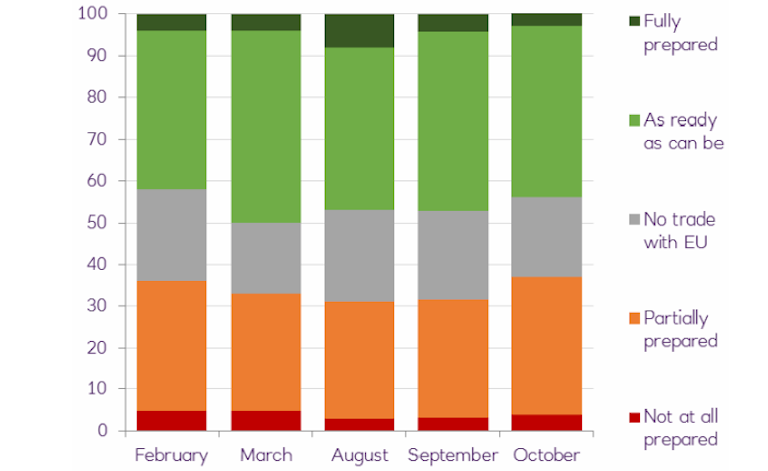

The UK-EU Trade & Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is, as expected, largely confined to trade in goods – zero tariffs, zero quotas on qualifying goods. To qualify for tariff-free access, British goods will need to meet Rules of Origin (RoO) requirements – some sectors are exempt and UK manufacturers are able to ‘cumulate’ (both UK & EU components count towards the RoO threshold). A 12-month grace period on some aspects of RoO declarations will give business some breathing room to obtain supporting documentation from suppliers.

The agreement does not secure broad mutual recognition and instead seeks to minimise technical/ regulatory divergence via the adoption of international standards and streamlined compliance processes. This means British goods entering the EU will need to comply with EU law (and vice-versa) so many goods will face two sets of conformity assessments, thereby adding costs to business. While the deal requires new customs declarations & paperwork for GB & EU trade, a ‘trusted trade scheme’ will allow for a simplified process for eligible businesses.

How will UK corporates & markets adjust to the post-Brexit landscape? Listen to our latest episode of On Point on Spotify or YouTube to find out.

Trade in services

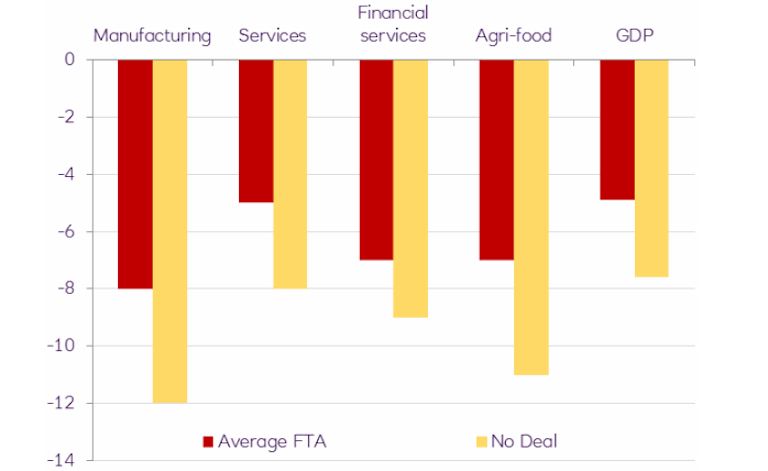

Other than limited provisions for airlines, hauliers, and telecoms providers, services are largely absent from the deal – with layers of complexity stemming from national variations within the EU. The services provisions do include a ‘Most Favoured Nation’ (MFN) clause which, in principle means that, were the UK or EU to give more favourable services terms to a third country in future, those terms would automatically extend to the UK/EU.

For financial services, the agreement amounts to a ‘no deal’ outcome. EU financial passporting has gone and the once hoped for ‘enhanced equivalence’ is proving elusive. Fortunately the sector had prepared for this outcome: around 8,000 financial services jobs and £1.2 trillion of assets have been relocated from the UK to EU centres since 2016, according to EY.

Instead, the UK & EU have agreed to establish a framework for regulatory co-operation, and negotiations on financial services equivalence are to begin imminently with a view to reaching a deal in some form by March 2021. The EU agreed to extend the current arrangements for euro-denominated derivative clearing, but this appears aimed at buying time to construct rival infrastructure. Still, for the fund management sector, uncertainty persists around the extent to which ‘delegation’ is permitted.

How will the end of the transition period affect the way companies in the UK and EU access financial services? Click here to learn more.

Level Playing Field (LPF), competition & taxation

As for LPF, the TCA’s provisions fall short of EU demands for the UK to align with EU law but go beyond those in the EU’s trade deal with Canada, and the EU subsidy regime will no longer apply in the UK. The TCA defines subsidies along with common principles on processes and exemptions, and makes specific provisions to deal with any dispute – if a dispute cannot be resolved by consultation, independent arbitration is an option, and each party can impose remedial measures if either assesses the rules to have been breached.

Both sides have committed not to lower existing overall standards of labour and social protection vis-a-via trade and investment (‘non-regression’ agreement), and have the right to take countermeasures – tied to harm caused to trade – if the other side has engaged in unfair practices. Tying any countermeasures to harm to trade may limit how these provisions are used, but this still creates uncertainty over where divergences might arise (and what retaliatory action might ensue).

The TCA sets out common principles around competition policy, and provisions on taxation are very limited (essentially confined to not lowering standards below what has been agreed in the OECD) – neither are subject to dispute resolution. But the deal also includes a ‘rebalancing mechanism’ – to allow adjustments to be made in response to policy divergences over time from the agreed baseline, which could allow tariffs to be imposed and even (in extreme cases) a reversion to WTO trading terms.